To be adaptable sounds pedestrian, even boring, in a time where all sectors speak constantly about innovation as the ultimate individual and organizational capacity. Innovation is said to be all around us but simultaneously innovation still seems like something magical and far away that only mighty individuals or mighty organizations can attain – we aren’t all going to be Muhammad Yunus, Steve Jobs or Teach For America. While there is an argument to be made that adaptation and innovation are nearly identical because really very, very few products, services or processes are truly breakthroughs, but rather tweaks and adaptations of what already exists, that is more philosophical than I want to be here. I want to frame this post around adaptation because I think it helps bring the conversation closer to our lived challenges and aspirations in organizations.

Why do we care? We care because of the rapid pace of change and high level of uncertainty facing our organizations on all fronts. In some situations adaptability can mean survival in other situations it is a foundational pillar of excellence. An adaptable organization will by definition be a more resilient one.

Adaptation can arise through response to external factors (funding shifts, government policy, a new opportunity, a natural disaster) or from internal factors or considerations (strategic planning insights, retiring CEO, dare I say organizational learning!). The private sector has multiple systems to aid innovation (adaptation not a sexy enough term). There is the financing ecosystem from angel investing, through venture capital and private equity. Product innovation is supported by sophisticated market research, frameworks like customer centric innovation, and strategic and project planning. Specific financial tools such as net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR) and even more esoteric quantitative metrics exist to quantify benefits and costs for any new initiative. It’s important to note, lest we feel too left out, that these systems are hardly flawless (successful venture capital investments and successful product innovations occur at about the same rate, 10-15% of the time).

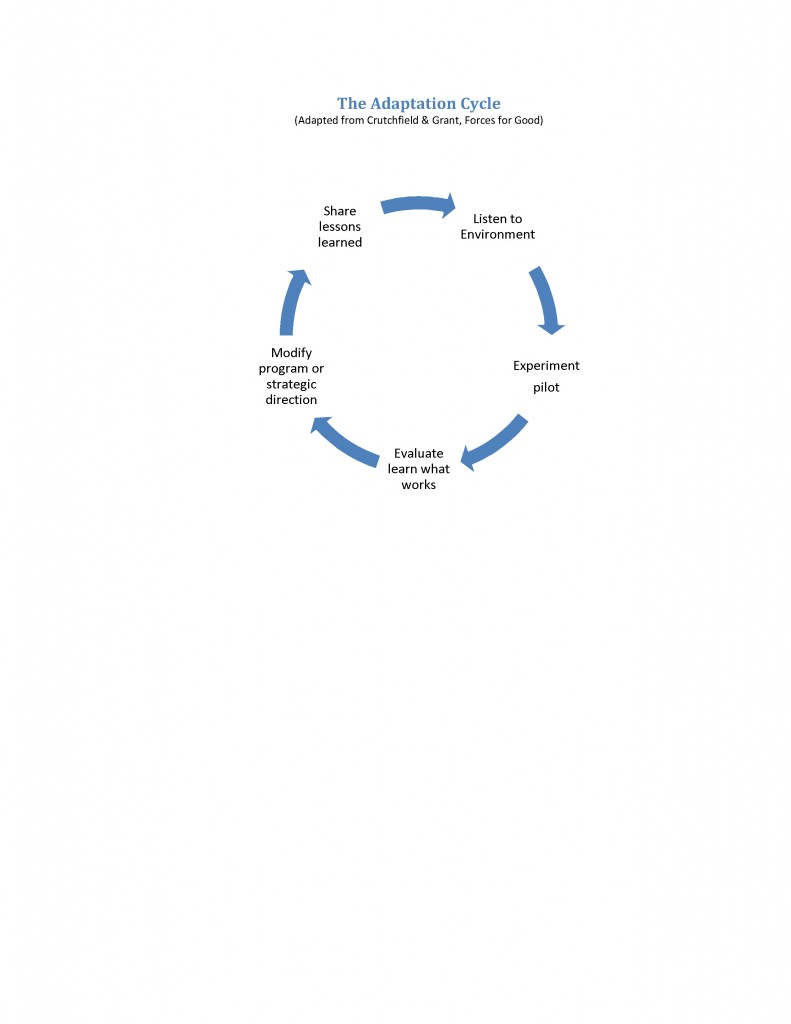

Finally before exploring the specifics of the virtuous adaptation cycle it is worth recognizing the fundamental tension that exists between the modalities of adapting and/or piloting new programs, products or processes vs. the behaviors that enable organizations to evolve routines and standards for effective execution. Managing this tension is an essential component of adaptive excellence.

Listen to the environment:

· Maintain large networks of formal affiliates and informal nonprofit allies. Large numbers of ties, even when they are weak or intermittent, is a stronger information gathering method than a tight inner circle.

· Larger organizations can listen via local sites or regional offices

· Work with businesses to stay tuned to the market

· Listen to your own clients, customers and funders *(an especially important topic and an upcoming post on its own)

Example from Intuit (listening through customers): They take documents from a real small business and the Intuit employees’ task is to take the documents and buy, install and use QuickBooks to complete accounting tasks. How do you do it?

Experiment: When organizations perceive new threats or opportunities they must adapt existing or design and pilot new programs and processes. One great method to encourage this type of innovation is to recruit staff with diverse professional experiences to avoid slipping into group think. Another method is to formalize cross team collaboration – breaking down silos between departments. For example a critical and under-utilized collaboration is finance, program and development staff co-designing the revenue model for new programs.

What should you have before you experiment? Staff proposing new ideas and projects should at a minimum provide (these will be developed further in the upcoming post on learning from clients and funders):

· Core benefit/core value proposition

· A positioning statement (for whom the product/service is targeted, the value they’ll derive, and how it is distinct-better than other or existing offerings)

· A perceptual map or customer persona describing whom is to be served – whose needs will be met?

At a maximum and depending on the scale of the intended project there should be a business plan with full financials. Consider this selection of key questions venture capital firms ask prior to investing and common mistakes of venture investments and you’ll be well on your way to a thoughtful approach to adapting programs or strategic directions.

Venture Capital: Key Questions

· Does management have the execution skills and experience?

· Is the product/service sufficiently unique to mitigate competitive pressures?

· Do the economics of the business/program support an attractive return on capital? In our sector this is a social return requirement and a sustainable financial model.

· Is the addressable market sufficiently large to justify the investment?

· Does the investment fit with the strategy and scale of the venture firm? Transform this to: “Does the project fit with the strategy of your organization?”

Most Common Venture Mistakes

· Management isn’t up to the job

· Insufficient expectations regarding the:

o Length of the product development plan

o Length of the sales cycle (cash flow issues)

o Intensity of the competitive response

· Not enough product/service differentiation

· Not enough capital raised

· Market not yet ready for the product/service

· Not admitting that you made a mistake

Evaluate and learn what works: This is a huge area and to cover comprehensively goes far beyond this short post. You can go beyond merely meeting reporting requirements for progress by thinking through:

· Are we measuring what matters?

· What is the learning that will enable us to run this program or process with excellence?

· Ask your funders to pay for data collection and the development of metrics that matter for meeting client needs better!

· Benchmark best practices – steal and adapt what works. Businesses are often willing to share practices with nonprofits that they wouldn’t share with direct competitors.

Modify program or strategic direction: Based on the cycle above make the changes. You need to connect your observations, planning and learning to program or process changes. Is your organizational culture up for it? In this stage another key component is deciding what not to do. Review the venture capital questions and ask:

· Is the indicated new program or direction critical to mission?

· Do we have the competency to do it well?

· Are other local groups working on it – are we really needed?

Share lessons learned: To be useful knowledge must be shared among networks internal and external

Next post – learning from clients, donors and competitors